Me and Ivaylo, post-interview in his apartment.

Our first encounter

On an unsuspecting Thursday afternoon in the capital of Bulgaria, I met my nationalist friend Ivaylo in my local supermarket. He was working behind the till, and I was getting some lunch items.

I didn’t know he was a nationalist of course, it’s hard to tell what someone thinks based merely on their looks.

But within the first minute of talking to Ivaylo, I was pretty certain he was a nationalist.

As my groceries were moving towards him on the conveyor belt, I approached him with a friendly ‘здравейте!’

He immediately clocked my poor Bulgarian pronunciation, and hit me with a direct:

“здравей! You are not from here, are you?”

A statement with which I could only agree.

“Are you a tourist, or are you living here?”

I explained to him that I was living in Bulgaria, albeit only recently.

‘Ah, that is good,’ he replied with a sympathetic smile, ‘we need more immigrants like you. You know, white immigrants. We already have too many gypsies and Muslims.'

The local supermarket where we met

I thought that was quite a forward way to start a conversation. But his demeanor was very open and friendly, so I still walked away feeling positive. I felt a little bit shocked, but in a weird way, I also felt welcomed.

It's unlikely that we would've become friends based solely on that initial interaction.

If it wasn't for a very random second encounter, a few weeks later, we would probably not have spoken to each other again. But this second encounter was so random that I interpreted it as predestined.

This was the situation: I was looking for a map of the Stara Planina mountains, for a long distance hike B. and I were planning to do. I had tried various booksellers in vain, before I found myself in front of a tiny little bookshop by accident. It’s not marked on Google Maps as a bookshop, but it clearly had ‘книжарница / bookstore’ written on its facade. And thus I entered this small 5x3 meter space.

The very special bookshop

Inside there were two people. The bookshop owner, and my friend Ivaylo. Pleasantly surprised we both greeted each other as old friends. We shook hands and he introduced me to the bookshop owner. Once the bookshop owner realised I was Dutch he immediately exclaimed:

‘Ah, Holland! Anton Mussert!'

Anton... Mussert...

Out of everyone that he could associate with the Netherlands — Johan Cruyff, Vincent Van Gogh, or even Mark Rutte — he choose the leader the Dutch nationalist party of the 1940s.

And then it dawned on me.

This was not an ordinary bookshop.

This was a Nazi bookshop.

Everywhere around me were Nazi books. Biographies of prominent SS’ers, fascist headpieces, and most prominently on the presentation table: Mein Kampf.

Holy fuck.

I was confused. Ivaylo is such a friendly person? Even here in this bookshop, whilst I came to the realisation that my friend was a Nazi, he continued to be friendly and gallant.

So I asked him straight: ‘So.. you guys are like… Nazis?’

They laughed and explained that they prefer the term ‘nationalist’. Ivaylo then continued to proudly show me the logo of Bulgarian nationalism that covered the width of his t-shirt.

I was a bit weirded out by this interaction, so I asked them: 'You guys know the Nazi's were the bad guys, right?' To which they replied: 'Ah, but you know that the Bulgarians fought on the side of the Axis powers, right?'

I had to admit that I didn't know about that. In fact I hardly knew anything about Bulgarian history.

But I was eager to learn. So from that moment onward, every time Ivaylo and I would meet -- whether that was in the supermarket or for drinks in the park -- we would discuss Bulgarian history.

On becoming friends with a nationalist

By talking to Ivaylo, I've learned a lot about Bulgarian and Balkan history. My new friend proved to be a knowledgeable teacher, who has studied history at the Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski and who has done intensive personal studies besides that.

You as the reader might now be thinking: 'Yeah, but Jaer, you've obviously been listening to a far-right view of history. The stories will be twisted to fit an evil point of view, don't listen to him!'

If you found yourself thinking something along those lines, I would like to ask you the question: What is so wrong with merely listening to someone's story? What is wrong with getting to know someone, learning where he's coming from, and understanding his worldview a bit better?

Many people dismiss far-right nationalists as 'dumb', or 'evil', but Ivaylo has always been a kind and intelligent person to me.

That might sound surprising, no?

The far-right is always accused of generalising, putting people in boxes, and hating groups without knowing them.

But how much of that applies to us too?

How much of what you know about Nazis, fascists, and the far-right have you learned from indirect sources? How often have you had a genuine conversation with one of them?

Probably not very often. So this is your chance! In this interview you can finally get to learn a far-right nationalist yourself, just like I have done over the past year.

This interview is not an attempt to normalise far-right ideology, but neither it is an attempt to fight it. I see it more as a descriptive document, where I pen down a piece of my personal history, and a piece of Ivaylo's history. I try to be somewhat neutral, but when it comes to certain nationalist ideas I have to display my dislike (it's still my blog after all :) ). Even though the document is intended to stay relatively neutral, your take-away from it might not be. If anything, I hope you will take away something valuable, and that you might learn a bit more about Ivaylo, nationalism, and Bulgaria.

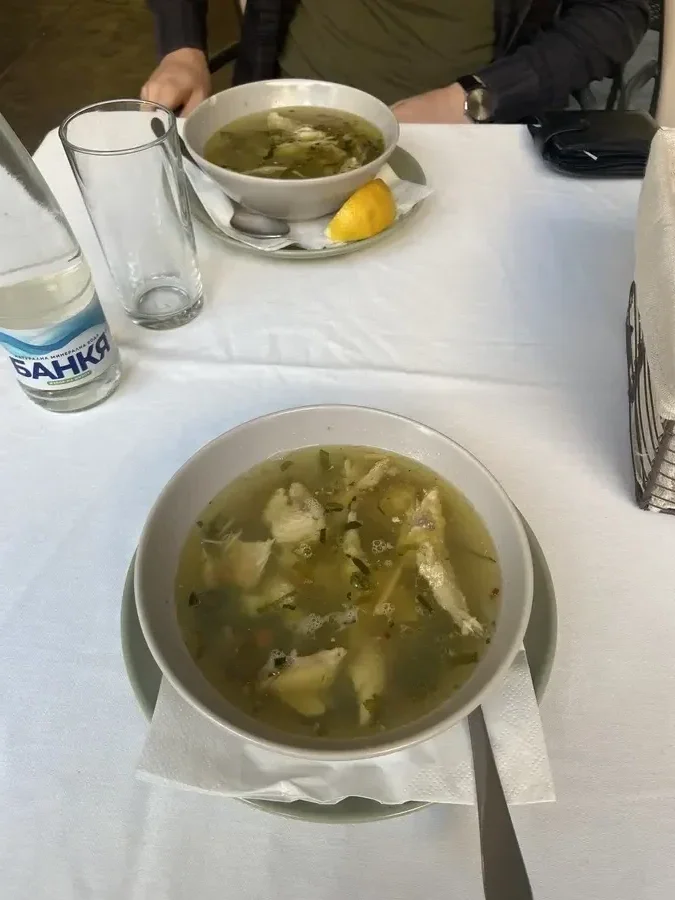

So yes, that's how I found myself in a restaurant in the Bulgarian Black Sea city Varna.

About to eat nautical soup with a nationalist.

Our lovely fish soup

We're sitting opposite each other on this otherwise almost empty terrace. Once I've hooked up my own microphone, I watch Ivaylo do the same with his mic. While he's installing the microphone, the implications of this interview seem to dawn on him.

'Oh, and just to ask you, how many of the questions are going to be political?'

This is a good question. In all honesty, I didn't prepare any questions for this interview. I tell him that we'll just chat and see what topics will come to mind. But knowing Ivaylo, politics is never far away from his mind. My primary interest is his life, so it seemed logical to me that we start at the start: his youth.

Growing up in post-socialist Silistra

Talking about Ivaylo's youth has to start by setting the scene. Ivaylo was born and brought up in North-East Bulgaria, in the border town of Silistra.

The city is situated on the banks of the Danube, and right across the river you can see Romania. A town’s proximity to the border can be very beneficial for its economy and culture, especially when paired with one of Europe’s most eminent waterways

Unfortunately for Silistra, the position of regional powerhouse on the Danube is already taken up by the city of Ruse, some 120KM land inwards. Ruse is the place where there the Soviets build the so called Friendship Bridge (Mост на дружбата) in 1954 - the only bridge connection between Romania and Bulgaria at that time. A second bridge crossing was built only 59 years later, in 2013, on the other side of the country.

You can understand the impact of this bridge on the economic landscape of North-East Bulgaria. Ruse's trading route grew in importance, while Silistra's position dwindled.

On top of the recent decline of the economical importance, Silistra has always felt the effects of being a border city. During its long history, Silistra has had an even longer list of rulers. Most recently it has been part of Bulgaria (1878–1913), Romania (1913–1940), and Bulgaria again (1940–present).

The beautiful side of Silistra captured by Justine.toms

Then finally, Bulgaria's socialist regime (1946-1990) has not been kind to this city. It's the effects of this regime with which Ivaylo was confronted most growing up.

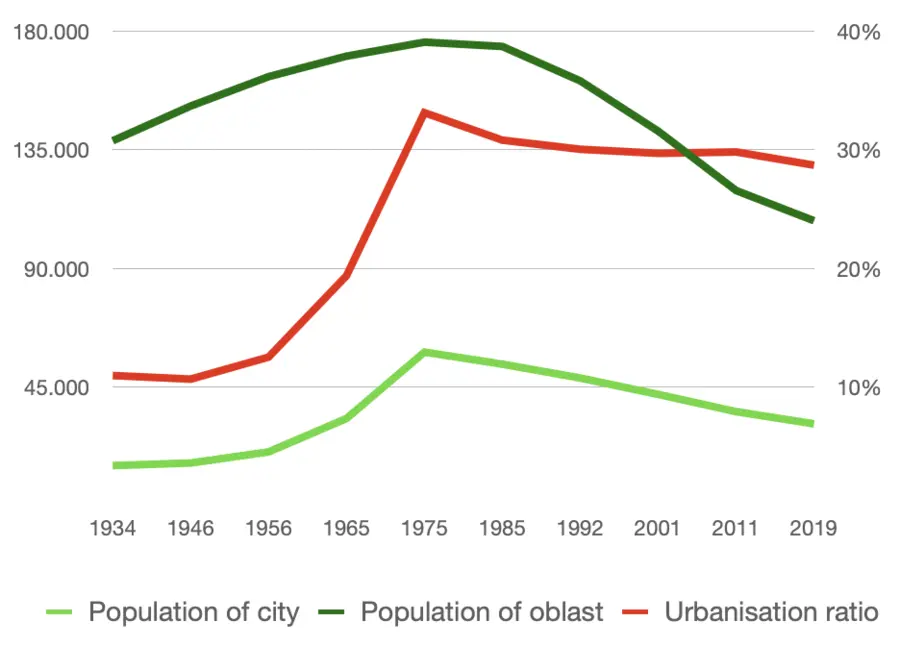

To give you an idea of the impact of socialism on the region, I present the population table of the city and it's parent province (oblast) below.

You'll be able to find that the urbanisation degree of the oblast was hovering around 10% before the socialist reign took off in 1946. Since that moment, the population was forced into the cities, at the cost of the rural surroundings. This made a large group depended on the state and artificial job creation, while it killed sustenance farming, further reducing independence from the state.

After the fall of socialism, the oblast of Silistra never recovers. Even though the population of the city is slowing going back to the pre-socialist era, the urbanisation degree remains skewed. The result is an overcrowded city and empty back lands.

Population of Silistra. Data via NSI.bg, quick overview can be found on Wikipedia

This is the context in which Ivaylo was born into in 1999. It's almost a full decade after the fall of socialism, but the effects were still visible.

"Yeah, it was not that good, you know? It was not that good."

Ivaylo goes on to describe his hometown:

"Silistra is very old city - the centre was built during the Tsardom of Bulgaria in a very European style; very German, very Austrian, very Dutch maybe. But outside this area it's like you're in Vorkuta, you're in Vladivostok, you're in Chokotka, you know - what the fuck? It looks like the type of towns you know from Russia, from the Soviet era."

A screenshot from Google Maps of the Iztok neighbourhood in Silistra (2012)

"The buildings are dark, the buildings are brutal. The people are too, because the people are seeing this every time. They see it and it changes their mentality. It changes you when all of this surrounds you."

After hearing these bleak descriptions, I couldn't help to ask him if he was also brought up in these type of dwellings, and how it affected him as a person. He confirmed that, even though he was born in a house, he later moved to one of the dreaded panelki buildings. Instead of letting the dark and brutal buildings dictate his youth, Ivaylo spend most of his time in nature.

"Yeah, I grew up in nature. The nature is very good around here. And we would go to the villages to visit our grandparents a lot. One of my grandmothers lived close to the Srebarna nature reserve. So I had a fun youth, a normal youth."

Character as a child

I want to know a bit more about his youth. What type of kid was he growing up?

"I was a bit of an aggressive guy. I was always for justice, you know? I had this strong feeling of defending the people that never had the strength to defend themselves. My childhood was mainly football, building stuff, and destroying stuff. Sometimes we would sneak over the border into Romania, I did that two or three times. But we were already in the EU. It was not a problem for the officers of the Romanian border."

Even though his youth was 'normal' and 'fun', Ivaylo cannot help reflecting on the shadows of that time.

"Now it's better than back then. Back then, you know, everything was shitty"

"We had nothing new coming into Silistra. There were no new sports coming in, no new atmosphere. Everything is old, and everyone has an old mentality. I wanted to train MMA there, but there was no opportunity for me."

It seems to me that Ivaylo made the best of his youth, despite the bleakness that surrounded him. The bleakness could be directly related to the only ruler the area had known for the last five decades: the socialists. It will therefore not surprise you that Ivaylo grew up with a strong dislike for the socialist era of Bulgaria.

Interest in history

Since Silistra lacked any form of present day excitement, or exciting future prospects, Ivaylo had to dive into the only remaining direction: the past. He became obsessed with learning everything about history. He vividly remembered how his fifth grade teacher introduced him to his favourite subject:

"I was listening to some of the battles, I think from the Serbo-Bulgarian war, and I started to get interested in what she was saying. And then I started to read, to read, to read, to go into the depths of Bulgarian history, and European history."

It was this interest in history that eventually lead Ivaylo to formalise his studies at the Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski. He was excited to move to the big city, as "there was nothing to do in Silistra".

Moving to Sofia

Moving to Sofia is what's on most 18-year-olds’ minds in Bulgaria. About 20% (1.3 milion) of Bulgaria's population (6.4 milion) lives in the capital. Half of the young people aspire to move to the big city, and the other half decides to flee abroad. The result is a massive brain drain and a strong population decline. This is clearly visible when you explore the Bulgarian countryside. Villages are empty and dilapidated.

Picture of the village Paramun. Photo by Ivan Bakalov

The neglect of the Bulgarian villages is so strong, that even the Romanians I spoke to on my travels looked at the situation with pity.

When I shared this observation with Ivaylo, his response was: 'Normal, normal, I understand them, I understand. They don't enjoy going to Bulgaria as much as going to Western Europe.'

Dobrudzha monologue

After Romania is mentioned, Ivaylo sees an opportunity to educate me on the entire Romanian-Bulgarian relationship:

'We were in the same block, you know, the communist block. We were on the same side during World War II, but we had some problems because of Dobrudzha [territory spanning the Romanian-Bulgarian Danube-delta], and historical problems during the Balkan War.

Map of Dobrudzha (dark green). Silistra fall on the border of South and North Dobrudzha (and Bulgaria/Romania).

We Bulgarians were far outstretched at the hardest front from Odrin [Edirne] to Istanbul. We were basically at Istanbul. The Bulgarian Army mobilised I think 800.000 or maybe one million troops. And our population was only four or five million. So yeah every second man was on the front because of the patriotism and because of the hatred for the Ottomans.

That was the first Balkan war, but Romania was never in the First Balkan War. They were in the Second Balkan War. The Second Balkan War was Bulgaria versus Greece and then also against Serbia. We nearly beat them and then Romania came and stabbed us in the back.

They nearly took our capital because all of our soldiers were near Belgrade, and near Solun [Thessaloniki].

This is the thing in history. The most aggressive, the guy with the most strength, he has the right to take this land. This is nature, you know? This is the thing with armies.

So Romania wanted South Dobrudzha, and they took it. They occupied my region till World War II but Hitler gave it to us again you know.'

King Boris III of Bulgaria, meeting Adolf Hitler of Germany. Nazi Germany mediated the Treaty of Craiova that gave South Dobrudzha back to Bulgaria. Photo via United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

It is during these monologues that I notice Ivaylo's passion for history. It also gives me an indication where his nationalist ideology might've sprung from. Once you start digging into the history of your own region, you will start feeling more connected to it. You might feel certain emotions about things that happened a long time ago, because it happened to your ancestors.

So when Hitler gave South Dobrudzha back to Bulgaria, it puts him in a positive light. And when the socialist regime negatively impacts the region in the 20th century, then that is personal too.

Slowly but surely, I start to understand how Ivaylo warmed up towards nationalist ideologies.

Three career options

Following his passion, Ivalyo decided to move to Sofia to study history. This seems logical, but it doesn't mean that history was his first choice.

"Firstly I wanted to become a footballer, like every European boy, but then because of corruption, I had to remove that dream."

He explains to me how Bulgarian football teams are often run by shady oligarchs and organised crime. The leadership of these clubs is mostly concerned with extracting as much money as possible, without any regard for the future well-being of the club or the talents.

If you are interested to read more about the corruption in Bulgarian football, I recommend this long-read on Breaking the Lines. They summarise the Bulgarian football situation as follows: 'a fish rots from the head down,' and that seems to correspond with Ivaylo's view on the matter.

After football was crossed off the list, Ivaylo quickly found another potential career path:

"I then wanted to become a soldier, but the same thing with the corruption. The military right now are not like back then. They used to fight for ideals, for the country. But right now they are there just for the salary."

I asked Ivaylo what intrigued him about the military.

"It's because of history. I wanted to go in this atmosphere, to feel what it is to become a soldier, you know, but the Bulgarian army doesn't provide you to become a soldier right now."

Okay, so no military, because of corruption?

"Yeah, but I think the things of corruption and the things of the state, they should change. They could change at the 180 degrees, really fast, at war, you know? This is a normal thing at war. I think it was some sort of a quote, I think maybe it's Joseph Goebbels's: "The war puts everyone in their right place." So yeah, I don't say that we need a war, but yeah, we need a war."

By that logic, a grand event like a war would be beneficial for the Bulgarian nation, because it would root out the corruption and put everyone in their right place. It makes me wonder, if there ever would be a war, would Ivaylo join the army then?

"Oh yeah, yeah."

To me this was interesting, because if I ask that question in the Netherlands, most people would respond: 'No, of course not, are you crazy?!' On the contrary, people in the Netherlands much prefer to discuss what neutral country they would flee to in case of a war.

But how would my Dutch friends have responded if their country was among the poorest in Europe and riddled with corruption? Would they not have longed for a big sudden switch of society? A big shake up that would 'put everyone in their right place'? I wonder about that, while I ask Ivaylo about his third career option.

Studying history

Since football and the military have been crossed of the list, the last remaining option was studying history. In 2018, Ivalyo moved to Sofia and enrolled in the Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, majoring history, with a pedagogy profile.

University of Sofia St Kliment Ohridski. Photo via Medlinkstudents

So if Silistra is the place where Ivaylo's ideas had sprung, then Sofia is the place where the ideology really matured.

'It developed more in Sofia, yes. Because Sofia is the capital. Two days ago I was looking at the map and I thought: No, Sofia is not a capital of Bulgaria, because it's not in the centre. It's bordering Serbia, and it's very close to Romania. But when you add Macedonia [to the map of Bulgaria], when you add Zapadni Pokraĭnini [Serbian territory where many ethnic Bulgarians live] then Sofia is near the centre of Bulgaria.

And because it's in the centre, many Macedonians came there, many Bulgarians from Serbia, many Bulgarians from Hungary came here. And now I know a lot of people from these regions. They've added some ideas to my view, and I've added some ideas of mine to their view. So yeah, Sofia made me the person I am right now. I lived there 8 years, it's like one third of my life.'

Map of the former Western Bulgaria Outlands. Map via Wikipedia.

So just like any capital city, Sofia serves as a meeting place for people from all over the country. Ivaylo specifically mentions that he met many ethnic Bulgarians from former Bulgarian territories. They must have shared their experiences of growing up as a minority in a foreign country, when the people of your own ethnicity live just across the border. These experiences are very close to home for Ivaylo, as he grew up in South Dobrudzha, the region that was in Romanian hands only 85 years ago. He still has relatives in North Dobrudzha (present day Romania) that are ethnically Bulgarian, but whom he has never met before.

The experience of living in these border territories must be very complicated, especially considering the dynamic nature of these borders in such recent history. I can only imagine what emotions must have charged the conversations that Ivaylo had with his fellow border Bulgarians.

Issues with communist teachers

As you might understand by now, Ivaylo clearly has a passion for history. He can enthusiastically talk about it for hours. But passion and enthusiasm are not always enough to get a diploma. After four years at the university, Ivaylo left the institution without a degree. He once confided in me that this was due to some personal issues with a communist professor. During this interview, I see an opportunity to ask him about the status of this issue.

"Oh no, I still have a problem with him. He's more of a political guy than teacher. You know, in his own words, he is a socialist. He looks like Lenin. Maybe he's gay too."

I didn't know that Lenin was gay?

'Ah, he was a passive one.'

Statues of Lenin, collected in Sofia's Socialist Art Museum. Photo by toonsarah-travels.

So what was the issue that couldn't get resolved?

"I had to go to an exam and if you want to go to the test, you have to pay 50лв [€25] for the protocol. So I bought the protocol and when it was time to do the exam, the protocol was there, but the teacher did not show up."

As someone who knows nothing about the Bulgarian educational system, I didn't really understand the implications of this. Surely there would be a solution to that situation, I thought. So I decided to dig a little bit deeper: 'So why does he have a problem with you?'

"Not just with me, you know, but with all the open-minded and outspoken nationalists. Yeah, you know, for example, he looks like Lenin, you know, for fuck's sake.'

Did you tell him that?

'It's not normal, yeah, it's not normal.'

You told him he looks like Lenin?

'Yeah, but I think it's a compliment for him. He's like Karl Marx, you know. He's like Karl Marx, and Ulyanov, so Lenin. He's a Russophile, not a nationalist at all. And he has his own Youtube channel full of Russophiles, communistic-minded Bulgarians."

So what did you do to piss him off?

"Nothing, you know. He's so intelligent that he recognises your ideologically. You know, I'm not a Christian, I'm a pagan, I'm wearing my amulet, or my T-shirt with runes. And some of these runes are in the SS, for example. And he knows this, because he's a doctor. He's a Russophile. He studied a lot of World War II."

An amulet of the Pliska Rosette, similar to the one that Ivaylo wears in first image of this article.

Okay, I have a question about the runes. Do you wear them for the paganism or for the…

"Paganism, yes paganism."

Or is it also a bit to provoke, maybe?

"No, no, no."

Aha, so did the teacher confront you about the runes?

"No, but he knows, he remembers."

So you didn't have an altercation, you didn't talk to about it?

"No, no, no, nothing about it."

You said you called him Lenin?

"Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah."

How did he respond to that?

"No, no, I told him that he sounds a little bit like Lenin, you know. And his vision is like this, you know? But a little bit. And because of this, I've told to you that he's very intellectual, you know, very intelligent. And he sees your view. He knows what you are talking about in between the classes."

"But that guy that looks like Lenin, he's the better version of the other one. The other one is a ferocious commie. This other teacher was like pro-communistic, and she's propagandising communism. What the fuck? Is that normal?"

I can see that as someone who grew up in a town that still suffers the consequences of socialism, that any intellectual discussion about communism might seem futile.

These ideological differences have lead to real-life consequences however, because without a degree, Ivaylo struggles on the job market.

"Right now I'm a history teacher with a license, but I don't have a baccalaureate. Which is bad. I can still become a teacher, many Bulgarians become a teacher without a baccalaureate. They can start but only with the right connections."

Ivaylo told me that despite lacking the right connections, he still received a job offer from a small town school.

"I said yes, but you know that the normal salary of a teacher is like 2000лв [around €1000]. But they wanted to give me half [so €500] because I don't have a baccalaureate."

You can now see the impact the ideological differences at the university have had. Could that explain why Ivaylo has put his feet in the sand and persisted in his ideology? As a stubborn response to being opposed by his lecturers?

It must have been pretty confronting to be surrounded by a majority of progressive, left-leaning students and professors at the universtity. It's not exactly fertile ground for growing a radically different ideology. So where did Ivaylo meet like-minded people that helped him develop his ideology, if it was not at the university?

Meeting like-minded people

I remembered the nationalist bookshop where I had met Ivaylo before. He seemed to be friends with the owner, so maybe that's where he met more like-minded people. I ask Ivalyo how he found out about the bookshop and how became friends with owner.

"We've met at events before. In Bulgaria we have, like in the Netherlands too, we have memorabilia. It's like a remembrance event for the fallen generals, the fallen officers, the fallen politicians, from the past."

"You know, Hristo Lukov?"

"They had this memorabilia thing, you know with torches, and that's it. You know, normal things."

Hristo Lukov was a nationalist, anti-semitic Minister of War from 1935 until 1938. He was assassinated in 1943 by two communist resistance fighters. The Lukov Marches are considered highly controversial in Bulgaria, and have been banned since 2020.

Lukov March. Photo by Valentina Petrova

And you met the bookshop owner there?

"No, I will not share. I will not share, but yeah, he's my friend."

Okay, interesting. Why do you not want to say where you met? Is it some sort of secret meeting?

"No, no, it's a long story. It's a long story, but yeah, it's normal. You know, I think that Bulgarian nationalists have more common with democrats than the left-wing. Because for example we're on the same front with the war in Ukraine. Democrats and nationalists, we are pro-Ukrainian. And the leftists, you know, they are very pro-Russian."

Ivaylo steers the topic of conversation away from these meetings into a topic that he prefers to discuss: politics.

Political ambitions

Perhaps you might've already noticed it, but a lot of Ivaylo's life is connected to politics. Every topic we touch somehow manages to veer towards politics. It makes me wonder if he would ever want to become politically active.

"Maybe, yes, but only in the terms of nationalism. Not to become a politician of every colour, you know? Yeah, I have principles, that's it."

But surely still within the democratic system, right?

"No."

What do you mean? You just said a big speech about...

"I said that I'm more democratic than the leftists, in terms of the political spectrum. The democrats are somewhere a bit to the left of the centre. And I said that I was more democratic than the leftists, you know? But after my ideals are achieved there is not going to be democracy. Because this country doesn't need democracy. Because I think the democracy here is not really like a democracy. Our nation is not ready to become a democracy."

But you are a democracy at the moment, right?

"No, not in the full sense. On paper, yes. In practice, no. And I said to you that I have a lot in common with some of democrats in the line of Ukraine, in the line of European Union I want to be in the European Union, not outside, not with BRICS_. Fucked up minds, you know with North Korea, South Africa, these guys, you know."_

"We don't have a long history with democracy, you know, we've had a lot of changes. We either had left, or the right. And if the right is here, and the left is there, then democracy is maybe in the centre."

I'm slightly confused by this remark. How I see it, democracy is the playing field that we're playing at. And you can have left and right parties within the democracy. I share this with Ivaylo, and he replies:

"Hmm, that's a good term, yeah, yeah, it's a good term. I've never heard it."

Because what would be the alternative to not having a democracy?

"I think you have a lot of good and bad alternatives"

Would you lean towards anarchy or totalitarianism? Or something else?

"Anarchy? Oh, totalitarianism is the better opinion."

Totalitarianism is only better when you are at the top, right? Because if you are not, then you have nothing to say.

"No, no, no. For example, Tsarist Bulgaria was a monarchy, and it was quite totalitarian. It was not a dictatorship. Yeah, the Tsar's word was the last word, but he had a parliament of ministers. The Tsar was not taking decisions by his own but the ministers too."

But is it not a bit optimistic to say that?

"Yeah, it's optimistic. I think the state should contain special spheres. And I think that you should have professional unions. A union of the agrarians, a union of the teachers, et cetera."

Now I thought that was quite an interesting remark. It sounds very much like a socialist idea, so I reply saying: "That's quite a socialist idea."

Ivaylo agrees, but notes: "But it's also good in terms of nationalism."

I experience a light-bulb-moment and reply: "You know, maybe you can somehow combine those two..."

Ivaylo recognises my jest and smirks: "I don't know, I've never heard about this, I've never read about this, what is it called?"

I'm smiling too and reply: "I don't know, someone should come up with a name for that…."

After that short interlude joking around, it's straight back to business and Ivaylo continues:

"I think it's good to have unions, to have their leaders"

But union leaders are democratically elected, right?

"Yeah, it's a democratic system. So I am closer to democrats. But when my things are sort of designed, then we don't need… Yes, this is the playground, like you've said it: democracy is the playground. On the one hand you could be democrat, but the other hand the democracy is also the matrix, you know?"

I don't follow exactly where he's getting at, so I ask for clarification.

"The matrix, you know, the other side is the matrix."

I seem to recognise what he means. 'The matrix' is the term which many people on the right use to describe 'the system'. I tell Ivaylo that I see what he means, but that we still have to work within the confines of democracy, because it's the best system we have, you cannot get out of it.

"You may"

You may?

"You may, with totalitarianism."

Aha, okay. Yeah, but that's not… I mean... would you be interested in totalitarianism?

"I don't know, I've never experienced it, but you know it's better than anarchism. It's better than democracy. If you want a strong hand, if you want to strengthen your people and your ground. And your vision about your territory and ideals, then yes, totalitarianism.

This vision of totalitarianism matches with other snippets of ideology that Ivaylo has shared with me before. Views of 'a strong men', 'fertile women', and 'blood and soil'.

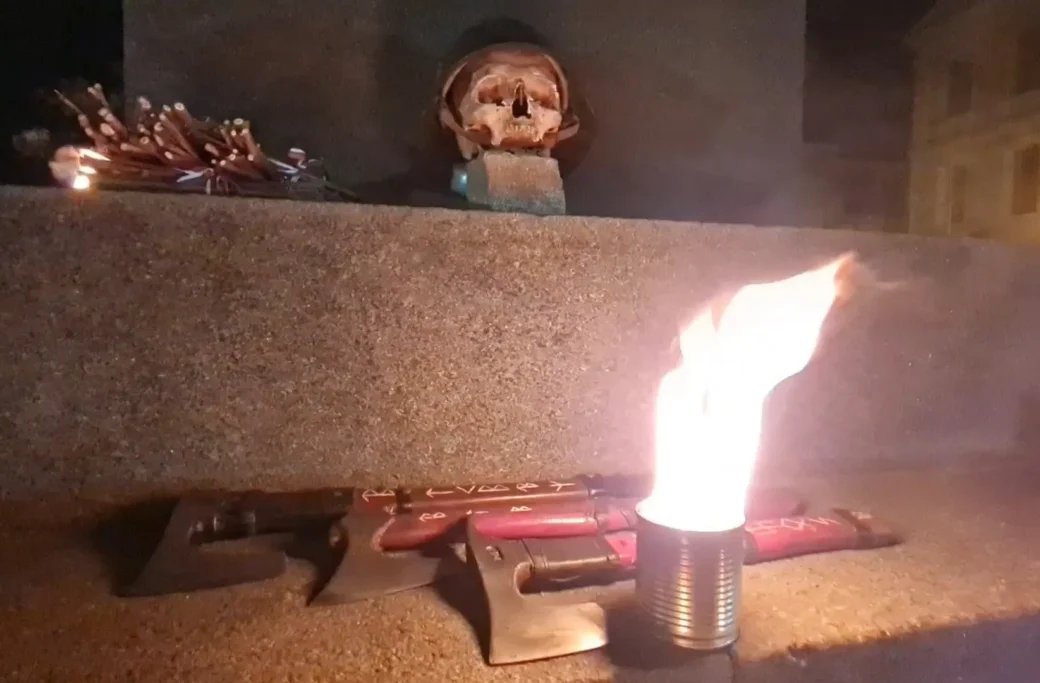

At some point after we've conducted the interview, Ivaylo shares a link with me that leads me to the website of the Bulgarian National Union. He didn't mention this party during the interview, but the page that he shared shows pictures the initiation of new recruits to the party. Reading more about this political party gives more insight into Ivaylo's political ideology.

Ivaylo in his role as officer of the Bulgarian Nationalist Union, present at the initiation of new recruits (holding the flag, second from the right). Photo via BNU website.

Membership of BNU

The initiation of the new recruits looks like something straight from a movie. The centre piece is a skull wearing a military helmet, surrounded by axes covered in runes, there are bundles of twigs that closely resemble the namesake of fascism: the Roman fasces -- 'a bound bundle of wooden rods, often, but not always, including an axe' (definition via Wikipedia).

Ivaylo has often spoken with disdain about the Italian ultra-nationalistic movement that we know as fascism. When I proposed to call this article 'I ate fish soup with a fascist' (I'm a sucker for alliteration), he was quick to correct my mistake. He is not a fascist, that's only for the Italians, Ivaylo is a Bulgarian nationalist.

Ivaylo explains to me that the bundles indeed look suspiciously similar, but that they in fact Bulgarian кубратов снопове, or Kubrate bundles. They are a symbol of unity and invincibility, inspired by Kubrat, the leader of Old Great Bulgaria.

Seeing these pictures shocked me a bit. I was aware of Ivaylo's beliefs, but I enjoyed entertaining them. I enjoyed our conversations, even though we disagreed ideologically. But even I have to admit that this ceremony looks rather sinister and evil.

I decided to read more about the party on their website. But what I read didn't really help me to feel any better. They use terms like 'traitors', 'political whores', and after they only managed to garner 3800 votes in their first national elections, they spoke of 'falsifications of the electoral results'.

Going to the personal website of the party's leader Boyan Rassate was even worse. Blog post after blog post, he is arguing that Hitler wasn't all that bad, defending the ultra-nationalist, antisemitic Bulgarian general Lukov, and calling the Sofia pride-parade 'part of a large-scale plan for the overall decomposition and destruction of the Bulgarian people'.

On the website of BNU he also proudly shares a full list of his arrests and the criminal lawsuits against him.

"There are a total of over 25 criminal law suits started against me; I have undergone a number of arrests and a search of my home and I have been judged several times for racism, discrimination, xenophobia and ethnic segregation."

Scroll to the bottom of this page to see the full bullet list, he introduces them with pride:

"Here is the full list of my arrests, court cases and criminal law suits, which I am very proud of though due to them nobody will hire me to work for the State."

A picture of Ivaylo holding the flag of the BNU youth organisation (Kubrat). The rune-like symbols on the green field are, according to their website, 'a stylised image of the number 14'. The number 14 is a popular number in white-supremacist circles, referring to Fourteen Words: 'We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children'.

Here's a short list of other things I found on the BNU website:

-

'Racial purity is the first and basic law of nature.' From the Youth Organisation

-

'Heirs of the ancient Aryans, not the monkeys of Darwin.' From the Youth Organisation

-

'We are a party that hates parties and wants their prohibition!'

-

'We acknowledge that the outcome of the battle we have started will not be decided peacefully through elections'

-

'The hordes of Xerxes, the hordes of Genghis Khan, the bashibozoks of Bayazid, the barbarians of Stalin and the apes of the Third World! These are the enemies of the Bulgarian people and our race!' From the Youth Organisation

Reflection on this interview

Seeing all these facts gathered on the page makes me very sad. I cannot say that I am surprised by it, because Ivaylo has always been very upfront about his ideas. Still it makes me sad. Reading the collection of all these evil thoughts hits differently than when Ivaylo said them in person. When I speak to Ivaylo, the controversial statements are always accompanied by an open smile and a pair of friendly eyes. I can't help to say that I have been charmed by him.

Ivaylo has never made a secret of his ideology. He has always been open to me. And I think it was his forthrightness that attracted me to him. Yes, his ideology is grim and evil, but his character is open and friendly. That might sound like a contradictio in terminis, but it is how I experienced it. It also makes me wonder how that duality affects him in his day-to-day life. Do people shun him for his ideology, or does he manage to charm his way through life?

Move to Varna

After 8 years of living in Sofia, Ivaylo recently moved to Varna. Varna is located on the Black Sea coast, in North-East of the country, relatively close to Silistra, where Ivaylo grew up. Varna is the third biggest city of Bulgaria (it only has 10K fewer people than Plovdiv), and boasts the country's biggest port.

Ivaylo moved to Varna because he 'wanted something new, because when I was in Sofia I was quite depressed, because of the state of the city.' So far the move has not been a great success. The switch from the hustle and bustle of the capital to the much smaller sea-side city has been somewhat anti-climactic.

'It's very hard. It's very calm here. The life and the Bulgarians here are very calm. All the good people from Varna go to Sofia to make it. They never stay here because the colour of the nation is Sofia. It's not that good, but yeah...'

It has also proved more difficult than anticipated to find like-minded people.

'They don't have a political opinion here. The people don't have political views, and they don't have a historical view here.'

When I ask Ivaylo if he managed to find a job in Varna to sustain himself, he shows me a glimpse of how his ideology directly impacts his life.

'Yes, I'm bartender here right now. It's nice, normal work. They are very tolerant to me.'

By saying that the people at his work tolerate him, he suggests that his views are not always met with tolerance. This suspicion is increased when we make our way back to his apartment, where he shows me the knife that he carries around.

I ask him why he carries a knife, to which he replies that it is for his enemies.

'Do you have many enemies?' I want to know.

'Yes', he says, 'everyone has enemies'.

When I ask if he knows these enemies personally, he confides in me that he doesn't know them personally, but that there are a lot of people who don't like his ideology.

It sounds like a scary and lonely place to be. When you have enemies that you don't know personally, and when you have to be careful what you say at work.

Does it mean that Ivaylo can only hang out with people that share his views? How do the people close to him react to his ideology? I decided to ask him.

Girlfriend

Does your girlfriend share a lot of the same ideas? Do you discuss them with her?

"Yes, but she's a woman. She's a woman and women have their own nature. They don't hate by nature. And they don't analyse by nature like us men. We are the driving power. I'm not sexist, I'm not at all. I'm just taking from history."

"Things are changing, yes. We have Meloni, for example Giorgia Meloni in Italy [Italian prime minister and leader of the nationalist-conservative party Fratelli d'Italia]. Things are changing, but not that much."

So do you and your girlfriend agree on most topics?

"Yes, with some things she agrees, but with some things not. My views about the women, maybe not.'

When I ask about his girlfriend a few weeks after the interview, Ivaylo discloses that the relationship with his girlfriend has sadly ended.

Football and sport

The final topic that Ivaylo and I discuss is football. After all, we're both just two simple European boys who grew up with a love for the game. You'd think that this is a rather neutral topic, but it soon becomes political again.

Are you still a football supporter?

"Oh yeah, yeah."

What is your favourite football club?

"In every country I support at least one. From Netherlands, none really. Maybe from the Netherlands Feyenoord is good."

Oh no... then we can't be friends I'm afraid...

"Yes, you are for Ajax, but Ajax is not a Dutch club I think. It's a very semitic club. It's like Tottenham."

"In Italy, I like Lazio"

That's a very fascist club too.

"I didn't know that. What a coincidence... I didn't know that..."

And in Bulgaria?

"In Bulgaria, Levski. It's a patriotic club."

Is it?

"Yes, they are with Lazio."

Ah, okay, that makes sense.

"I like Dynamo Zagreb. They are also with Levski and Lazio. Dynamo Kiev, Dynamo Dresden, Hansa Rostock."

Some of Ivaylo's favourite football clubs.

For each country, Ivaylo has a favourite football club. They all seem to be part of a right-wing alliance of football supporters. His list continues, until we hit France. Ivaylo does not have a favourite team from France, 'because I don't watch African football'.

I think this is quite telling. Every subject we touch upon in this interview, inevitably gets political. Ivaylo asked me at the start of this interview how many questions would be political, and I answered him in all honesty that it all depended on how the conversation would flow. After all, I had not prepared any questions.

But in his ultra-nationalist worldview, everything seems to be political. From your choice of partner, to your academic success, down to the football club you support.

Even Ivaylo's latest hobby, calisthenics, seems to be inspired by the nationalist ideal of a strong people.

Full circle moment

As I'm writing these final paragraphs, I'm left with mixed feelings. The more I learned about Ivaylo's ideology, the more my mood dropped. It has been disturbing to find out all the details, and to realise that is all very real.

I do however believe Ivaylo is a genuinely nice guy, and I enjoyed hanging out with him. He has always been very open and welcoming towards me. It just saddens me to think that my skin colour and gender had anything to do with that.

And even though I dislike his ideas, I can now at least understand where they are coming from.

I would like to end this article with a full-circle moment. During our first interaction, Ivaylo mentioned that he likes me because I was a white immigrant, not a Muslim or Roma. During this interview he circles back to that, providing more insight into why he might've been interested in hanging out with me.

"You're a migrant too, but you are working here. You have a wife. You're calm. You're not plunderer. We're going to assimilate you."

There is a real chance that if I had been in a different situation, with a different frame of mind, I would've been more susceptible to these nationalist ideas. Perhaps I would even have assimilated.

While I reflected on my possible assimilation, Ivaylo said something that concludes this article beautifully:

"Maybe if I was born like you, in the Netherlands, around that comfort, maybe eventually I would be like you too."

The soup

We now have to finish this soup story in style by asking, how was the soup?

'It was very good."

And I would have to agree. It was a good soup.