Today I had the honour to invite a special person to my soup kitchen. The lauded German-Russian chess master, and good friend of mine, Ronny Müller. Together we’re going to make a soup from his childhood, while we talk about his life and his chess career.

A bit about Ronny

Ronny was born in 1991 in Yekaterinburg, the fourth-largest city of Russia. Back then Russia was still part of the Soviet Union. One year after the fall of the USSR, Ronny’s parents decided to flee the country because they deemed the situation to be unsafe anymore. Food shortages had lead to hunger and chaos, which created a grim reality. People were forced to stay indoors and install many thick locks on the doors. Ronny recalls his parents telling him stories about how people were eating street-pigeons in order to survive.

Ronny disclosed that he does not have many memories of his time in Russia. Most of his upbringing took place in Germany. Growing up in as immigrant in Germany posed various challenges, but after a rocky start he does feel completely at home in Germany nowadays.

Like many young Russian boys, Ronny was introduced to the game of chess early on in his life by his grandfather. His talent was quickly recognised and he joined the local chess club at the age of 5. He went on to become the rising star of his Bundesland Saarland. At the age of 17 he became the youngest chess player to ever win the championship of Saarland, a record that he still holds to this day.

As a teenager he twice became runner-up in the German national youth championship, represented Germany at the European youth championships, and played against future world top-rated players (e.g. Nepomniachtchi).

Today I have invited Ronny over to make soup together and to ask him more about his life and his chess career.

Why is this soup special to you?

Now, let’s focus on our soup. Today we will be making a German potato soup. It’s a rich soup that can be eaten both as a full meal and as an appetizer. Besides the main ingredient (potatoes), it contains carrots, leek, celery, bacon, sour cream, and of course some German sausages.

Ronny explained that this is a typical German dish that his mum used to make when he was a kid.

‘I have actually never made this soup myself, but my mum is a professional cook. She used to work in an elderly home and prepare their food; breakfast, lunch, and dinner. And sometimes, when they had food left over, she would take some home for us. But I’ve not had this soup in a long time. I think the last time was when I was still living with my parents, I was 7 or something. Maybe 6.’

I thought it was interesting that he chose a typical German soup, and not a Russian classic like borscht. When I confronted him with this observation, Ronny explained to me:

‘Yes, that is also a good soup. We used to eat mostly Slavic foods at home, not just Russian, but all sorts of foods from Eastern Europe. My mum loved trying out new recipes, so she would experiment with all types of different Slavic dishes. I remember some specific Uzbek dishes that were really nice. Big stews, made on an open fire. My dad purchased a massive wok specifically for these dishes.’

Growing up as a Russian in Germany

While we were talking about the different cuisines that he was brought up with, I became intrigued by the clash of both cultures. Did this clash limit itself to the kitchen, or did it impact other aspects of his life as well? How is the life of a Russian immigrant, growing up in Germany?

‘It was a bit weird sometimes. Because even though I went to Kindergarten and school in Germany, my German was not as good as the kids in my class. At home we would speak Russian. But also my Russian was not perfect, because I would not speak it outside of my family situation. So I spoke two languages, but neither of them perfectly. It made me feel like an immigrant sometimes. But I think we as Russians were quite easily accepted into German culture. Germany is an easy country to integrate into. Everything is well organised, and it’s a rich country, so that makes things just easy.’

Learning chess

Ronny was introduced to the game of chess at a very young age by his grandfather. Both him and his sister were introduced to the game around the same time, but Ronny showed an early aptitude that stood out. He enjoyed playing these friendly games against his grandfather and later also his father. Both his father and grandfather never had any formal chess education, so when Ronny joined an official chess club at the age of five, it was only a matter of time before he would surpass them in chess knowledge. He recalls that this moment happened when he was around six years old.

Personally, I’m having trouble visualising a six year old beating his father and grandfather in a complex game as chess. How is this possible? Isn’t chess supposed to be a rational game of intelligence? How can a six year old beat adults in that field?

‘It’s because they’ve never had proper training before. They have only learned by playing the game. If you learn like that you will only occasionally notice that you made a bad move, or that your opponent made a really good move. But if you are in a chess club, you have dedicated lessons for dedicated topics. You learn strategies, tactics, and you learn to identify motives and patterns. The coaches will tell you “okay, you’re lacking in end-game against Rook”, and then you will go and study that particular situation until you master it.’

Talent recognised

Okay, so with a bit of training even a six year old can beat full-grown adults. No biggy. But how is the atmosphere in such a chess club full of six year olds? Are they beating adults left right and center, or did Ronny stand out at that age already?

Ronny explains that he suspects that he stood out by some degree, because early on in his chess career he got a personal trainer and he was invited to special state-funded training camps. By the age of 7 he had won every tournament for kids under 10 years old in his local area. From that moment on it became increasingly clear that he would become the best chess player of his region. And at the age of 17 this prediction was materialised when he won the chess championship of his Bundesland Saarland. He went on the win this championship for a total of four times (2008, 2011, 2012, 2015), making him one of the most successful participants of this tournament’s history.

Trained by a legend

As his star was rising, Ronny’s paths crossed with a very special individual. His name? Gennadi Nessis. Nessis was a world class correspondence chess player, who’s highest honour was the second place at the 1989 World Championship Correspondence chess. But perhaps he’s even more well known as the coach of Alexander Khalifman, the 1999 Chess World Champion.

Just like Ronny, Nessis was born in the USSR. But that’s not where the similarities stop, because as a stroke of fate Nessis also happened to live in Ronnys hometown of Saarbrücken. As a matter of fact: they lived just a few streets away from each other!

They bonded over their shared language and their love for the dragon opening, which lead to Nessis becoming Ronny’s personal coach for the next two years. Twice a week they would meet up and discuss chess. It is not surprising that these two years coincide with some of Ronnys best chess moments.

Proudest achievements

Under the guidance of Nessis, Ronny managed to achieve some of the proudest moments of his chess career. Most significantly are his victories at the championships of Saarland. Getting crowned champion of one of 16 Bundesländer also meant that he got a ticket to the German national championship, where he competed with the nation’s best chess players. To his regret he never managed to secure first place on this podium, but he can be proud of finishing second at both the national championships U10 and U12.

Next to his respectable podium placements at these prestigious tournaments, a few other things come to mind when he’s asked about standout chess memories. For example the time when he was captain and playing on the 1st board for his local chess club. Under his leadership the club achieved their first promotion to the 2. Bundesliga, one of Germany’s highest chess leagues. A memory he will not soon forget.

And then there is his draw against Ian Nepomniachtchi, a Russian chess player who ended up becoming one of the best players in the world. He is currently ranked number six in the world and he has won both the 2021 and the 2022 Candidates tournaments. The winner of this tournament gets sole access to challenging the reigning world champion in chess to a 14 game chess duel also known as the World Chess Championship.

When Ronny played against him on a cold October day in the small Russian city of Kirishi he was only 13 years old with a rating of 2075. Across the board sat the 14 year old Nepomniachtchi, who already was force to be reckoned with. The young fella boasted the title of International Master and had a rating of 2492. This massive rating difference makes it all the more impressive that Ronny managed to draw against him.

In the following years, Ronny would compete against other chess players that can now be found in the top 20 of the world. Names like Alexander Grischuk, Dmitry Andreikin, Ildar Khairullin, as well as famous chess commentator and former British chess champion David Howell.

Getting older

Talking about these achievements is very interesting to a layman like me. It is easy to get carried away by all of these big words. ‘What?? World champions?? National championships?? Wow, coached by legends?? Amazing!’

But what struck me even more is that Ronny didn’t seem to be too fazed about these memories. Yes, he verbally communicates his pride, but his demeanour doesn’t seem to correspond completely. His tone of voice stays plain and his descriptions are rather factual. Most people would light up when talking about their accomplishments and engage in a lively retelling of the emotions that accompany such events. But Ronny seems to lack that sort of energy.

It took me a while to decipher this juxtaposition, but I think I understand it now. It seems as if these memories are somewhat bittersweet to Ronny. Yes, they portray his biggest achievements in the chess world, but they also display how much time has passed since.

Most of these credentials were gathered in his early teenage years, almost twenty years ago. In these early teenage years he had all the time in the world to play chess and to improve. School was still fairly easy and he had very few other responsibilities. But as time advanced, so did life. He became older, got more responsibilities, and chess’ inexpugnable position in Ronnys life eroded.

It is important to note that Ronny’s very factual, matter-of-fact descriptions of his proudest moments can also be attributed to his humbleness or simply to his German inclination for factual storytelling. However, I do think it provides insight into his relationship with his chess history.

History is a difficult thing, and memories can be clouded. Each retelling of history is grounded in the present day, which infuses the memories with various other emotions and perspectives. But there are some things that don’t erode over time. Most significantly: love.

And it’s this love for the game that breaks through Ronny’s stoic front as soon as you ask any chess related questions. I specifically recall asking Ronny to explain his favourite chess opening (the dragon). He gets some extra pep in his voice and his hands whizz over the board. He turns into an engaged storyteller and starts sharing all the details, side-lines, and background stories of each move. To me that was a sign of deep love for the game. It is not about the past or his achievements, but the present and the game itself.

Rapid questions

In this section I will shoot a couple of questions at Ronny and he has to answer quickly.

Bishop or knight?

‘Bishop’

Open or closed game?

‘Open’

Opening or endgame?

‘Endgame’

Bullet or blitz?

‘Blitz’

Carlsen or Niemann?

‘Carlsen’

Germany or Russia?

‘Germany’

Black or white?

‘In general, or in chess?’

In chess

‘In chess it would be white.’

[Visibly confused] Wait, what do you mean ‘in general?’

‘In general it would be black.’

[Confused, and slightly concerned] ????????

‘I wear a lot of black clothes. Because I love metal music.’

[Visibly relieved] Ah, like that. Okay, that’s good.

On becoming a Grandmaster

It’s every young chess player’s dream to one day see the magical two letters ‘GM’ behind their name. However, the Grandmaster title is not obtained easily. The chess player needs to reach an rating of 2500, whilst also meeting various GM norms. A few examples of these norms are:

- The player’s rating performance at the end of a tournament must be at least 2600

- At least 33% of the player’s opponents must be grandmasters

- The player’s opponents must have an average rating of at least 2380

- The player’s opponents must come from at least 3 different chess federations

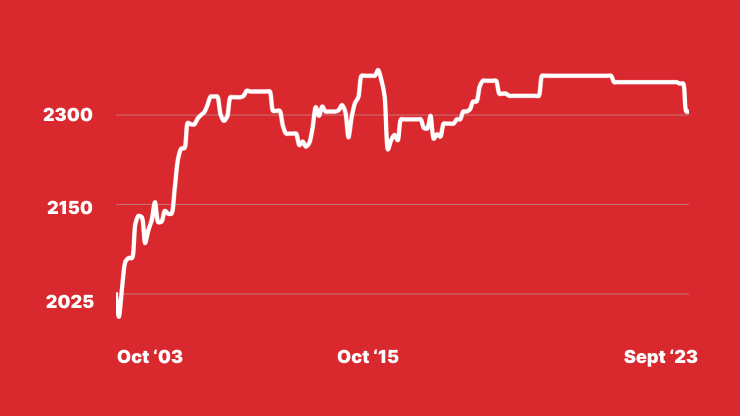

When inspecting Ronny’s rating progress chart on the official FIDE (International Chess Federation) website, you can see that his current rating (September 2023) is stuck at 2280, while his highest rating (2338) dates back to October 2015.

The first time that Ronny passed the threshold of the 2300 rating was in 2010, the year he was turning 19 years old. When confronted with this stagnation in his progress, Ronny’s tone of voice becomes a bit deeper. With an audible sadness he discloses to me:

‘Of course, it’s also hard for myself seeing that I haven’t improved my rating in over 10 years. I don’t think that this is the end, but I have to be honest with myself as well.’

I ask him why he thinks this is not the end. To an outsider like me it seems as if he has reached his natural plateau. That 2300 will be his final rating.

Ronny however, is not affected by my minor provocations. He continues to explain to me in a matter-of-fact manner that it is not a coincidence that he peaked at 19 years old.

Because this is also the time he was confronted with the choice of going to university or focusing on a full-time chess career.

Going to university

During Ronny’s high school days, he received special treatment, so that he could skip classes to attend chess tournaments. These chess tournaments (as well as the league matches that he would play with his chess club) are essential to growing your rating. This is where you will meet challenging opponents, so each of these matches requires tedious studying: checking your opponents historical records; what is his favourite opening? What does the theory say about this opening? What are his weaknesses? What opening should I use against him? And after each game you analyse; what went wrong? How could I improve my play?

All of this involves many hours of study and many hours of playing chess. A common tournament game can take up to 6 hours, and FIDE limits the amount of games per day at two. Add to that that a typical tournament involves playing 7 or 9 games and you can imagine the enormous investment of time that chess requires.

This was the reason that Ronny received special permission to skip classes at high school. He was a talented young chess player and he was doing well in school, so he could afford to skip classes.

But that changed when he turned 18 and was confronted with the dilemma to either go to university and get a diploma, or pursue a career in chess. This was not a decision he was happy to make, but Ronny also confides in me that it was not an excruciating dilemma.

Obtaining a university degree is almost a guarantee for your future, while there is no safety in pursuing a chess career. There is very little money to be made as a chess player, with the exception that you become a top 10 player. According to FIDE, there are approximately 1813 grandmasters in the world. But only a small subset of those grandmasters lives off playing chess exclusively. Most of them either have day jobs or they supplement their chess related income with teaching or writing.

So Ronny ended up prioritising his studies over his chess career. This didn’t mean that he quit playing chess altogether. He kept playing league-matches and tournaments for this chess club. But it became increasingly more difficult to combine the hardcore chess life with the life of a normal citizen.

Moving abroad

After Ronny’s university days were over, he received a job offer from a company in Dublin. Ready to take on this adventure, he moved to Ireland in 2016. This meant that he had to (temporarily) say goodbye to his chess club in Germany, but fortunately he was able to join a club in Dublin. This allowed him to continue playing league matches against other clubs, as well as the occasional tournament. He has always remained a loyal member of his German chess club (Caissa Schwarzenbach), even when he was living in Ireland and Malta. Even so much that he was sometimes flown back to Germany by the club to play on the 1st or 2nd board in critical league matches.

After two years of living in Ireland, his job brought him to the Mediterranean islands of Malta. But besides the sunny weather and the promising career prospects, Malta unfortunately doesn’t offer a great chess infrastructure like Ireland or Germany. There are no official league matches and there is no FIDE-rated classical chess tournament.

All of this amounts to the current stagnation in Ronny’s rating development. There are simply no opportunities to improve his rating on Malta. This is why Ronny has resorted to traveling abroad to attend chess tournaments over the last couple of years. But traveling abroad for a chess tournament comes with it’s own logistical challenges that further complicate Ronny’s journey to a higher rating.

The logistical challenges of a chess tournament

To illustrate how challenging the logistical side of a competitive chess career can be, we’ll have a closer look at the concept of a chess tournament.

A typical, run-of-the-mill tournament of classical chess usually consists of seven or nine rounds. This means that every player will play seven or nine individual games during a tournament. One game can take up to 6 hours to finish, because each player has 2 hours to play their first 40 moves. Once these 40 moves have been made within 2 hours, another hour of playtime is unlocked per player. Because these games can take such a long time, the organisation ordinarily only plans one or two games a day. This means that a tournament can span the entirety of a complete week in the worst situation.

Now imagine that you have a regular 9-5 job and you have to use your precious annual leave days to go and play a chess tournament. You might think: ‘Oh, well, you can combine it with a nice holiday then, no? Do some sightseeing, going to nice places during your time off.’ But the reality is that every free minute of such a week is spend on studying chess. Analysing the previous game, studying the next opponent, et cetera. If you take the tournament seriously, then all of your time will be consumed by chess.

It had never really occurred to me how time consuming these chess tournaments really are until Ronny told me this during the interview. I now understand that the journey to become a grandmaster is not simply about playing many games of chess, it is a holistic challenge that consumes the player’s life in a grandiose way. All other things in your life have to accommodate this goal. That’s a big sacrifice to make.

Staying sharp

It all sounded hugely depressing to me. Does this mean that Ronny has to give up on his dream of becoming a chess grandmaster? Is it just not compatible with his current life on Malta? I ask these questions to Ronny, to which he answered dully: ‘No, it is still possible. But yes, it would be better to move away from Malta.’ According to Ronny, chess players usually peak around their 30s, but their best years can be stretched until their fifties, before the effects of age really start to kick in. That would mean that there is no immediate rush to obtain the grandmaster title now. He can still enjoy his life on Malta.

But what does he do in the mean time? How does he stay sharp?

‘I study. A good example is when I play online blitz games and I encounter a surprising move by the opponent. After the game I will analyse the gameplay and especially that particular move. I’ll get support from the chess engine and do a deep dive into that move. Why is it a valid move? What is the plan? And what is the counter play?’

‘And also, what is very helpful, I think, is watching matches of good players. There are so many commentators nowadays that just go through particular matches or even commentate live matches. There are a few commentators that are top 10 of the world that would also have suggestions for people on my level, not only for beginners. It is interesting to see what the best people in the world play and then compare it to what you would have done in that position. It’s a great way to learn.’

Some of the commentators that Ronny recommends are Peter Sviddler and Peter Leko.

A bit more about chess

There are a few things I’ve learned during this conversation about chess that deserve a quick mention.

- People don’t tend to dress up strangely to distract opponents.

- Chess rooms can get quite stinky because of poor ventilation and the agglomeration of many sweaty players.

- Ronny has never tried to stick an anal cheating device up his bum.

- People bring various lucky charms to their chess table.

- Ronny doesn’t do lucky charms. He is German.

- Some people’s lucky charm is their t-shirt and they will wear it for the entire, multi-day tournament. Which explains point two of this list.

- Ronny has never heard anyone rip a massive fart during a tournament.

- But he has definitely smelled a few.

Having gotten these critical questions out of the way, we can continue with a question that will be of special interest to all of Ronny’s opponents.

What is your weakness?

‘I would say openings. Like I have my repertoire of different openings and variations I play, but I can still get surprised in a certain line that maybe I haven’t had to look for a long time.’

But openings are mostly theory, right? Does that mean that even after 25 years of studying this game you still haven’t mastered the theory?

‘The difficult part is that openings keeps evolving. New variations emerge. And chess engines keep getting better as well, so they will come up with new, better moves in certain positions. So you have to keep up to date, keep studying. But not just studying, you also have to apply this new material in matches, see how opponents react to the new move or the new opening, so that you get some experience with all the motives and all the pawn structures that can appear in this opening and so on. It’s a very dynamic world. This makes it hard to study, you can’t just pick up a book from the 80s or 90s and study it, because it will already be outdated.’

Does it ever get boring?

To wrap up this interview, I have to ask the question that has been on everyone’s lips. After playing thousands of games of chess, day-in-day-out, the same 64 squares, the same 32 pieces. Does it ever get boring?

‘No, because I’ve never had a game that was move by move the same. Sometimes you’ll have the first eight, ten, or twelve moves that will be the same. But at some point, your opponent will always do something different than other opponents that you’ve had before. I don’t think that I will ever stop playing chess in my life. And I think it’s the same for, I would say, most chess players.’

I thought that this very profound answer was a beautiful way to end the interview. It vividly encapsulates Ronny’s love for the game, and the attraction that millions of other chess players over the world share and have shared.

Soup recipe & review

Now finally back to the soup we made. Was it a great soup? Could I taste a bit of Germany in it? Let’s find out. Below you’ll find the ingredients, recipe, and my review.

- 600 gram of potatoes

- 1 leek

- 2 celery stalks

- 3 carrots

- 3 Wiener sausages

- Vegetable broth

- Bacon

- Crème fraîche

Recipe

The recipe is fairly easy. The pictures of all the steps are included in interview above. The first step is to chop all vegetables. Then you sauté them all (except the potatoes). After that you add the veggie broth and the potatoes. Purée everything to a smooth consistency. Add chopped up sausages and let it simmer. Finally you can add some fried pieces of bacon, crème fraîche, and chive as garnish.

Now what do I think of this soup?

Review

Frankly, I loved it. It is quite easy to make, even though it consists of many ingredients. This means you have to do a fair bit of chopping, but after that it’s fairly straight forward. It follows the classic soup formula: chopping, sautéing, boiling, puréeing. Therefore it gets an ease-rating of 4 star.

For the flavour-rating I’ll also give it a 4 star rating. The soup itself has a rich, earthy flavour profile that will so very well in autumn and winter. It’s rich in vegetables and contains a lot of macro-nutrients. I was especially happy with the chopped up wiener sausages in the soup. They gave a wonderful salty bite to the soup that elevates it to a 4 star dish. There is one thing I want to say about all soups that follow the tried-and-tested ‘boil veggies, then purée them’-formula: they run the risk of not differentiating too much from each other. Where they shine is their use of garnish. And this soup does taste really nice with the sausages, chive, bacon, and cream.

Bonus: Ronny vs Jaer chess game

As you understand, you cannot spend an afternoon with an passionate chess player without playing a single game of chess. So there you go: a few pictures of a game Ronny and I played while the soup was simmering.

And I couldn’t help myself but to include this little excerpt of the transcript that corresponds to picture underneath.

3:31:29-3:31:31 Good move.

3:31:31-3:31:34 Yes.

3:31:34-3:31:44 What I said is that this one…

3:31:44-3:31:48 …you found even a better move than I thought.

… but of course I lost the game anyway… 🙂