Most authoritative, fascist leaders have a suppressed theater kid deep down inside them. It is undeniable that they have a great sense for drama. Their fashion, their gesticulations, their choreographies, it all has something very dramatic.

But all of these leaders also seem to have had some artistic aspirations in their formative years. Hitler had his paintings, Stalin had his poetry, and even the contemporary Dutch fascist Thierry Baudet has published two romantic novels.

The question is: should we believe the narrative that they are all embittered, failed artists who seek their vengeance by committing abominable atrocities, or is an artistic disposition simply a prerequisite to becoming a great populist?

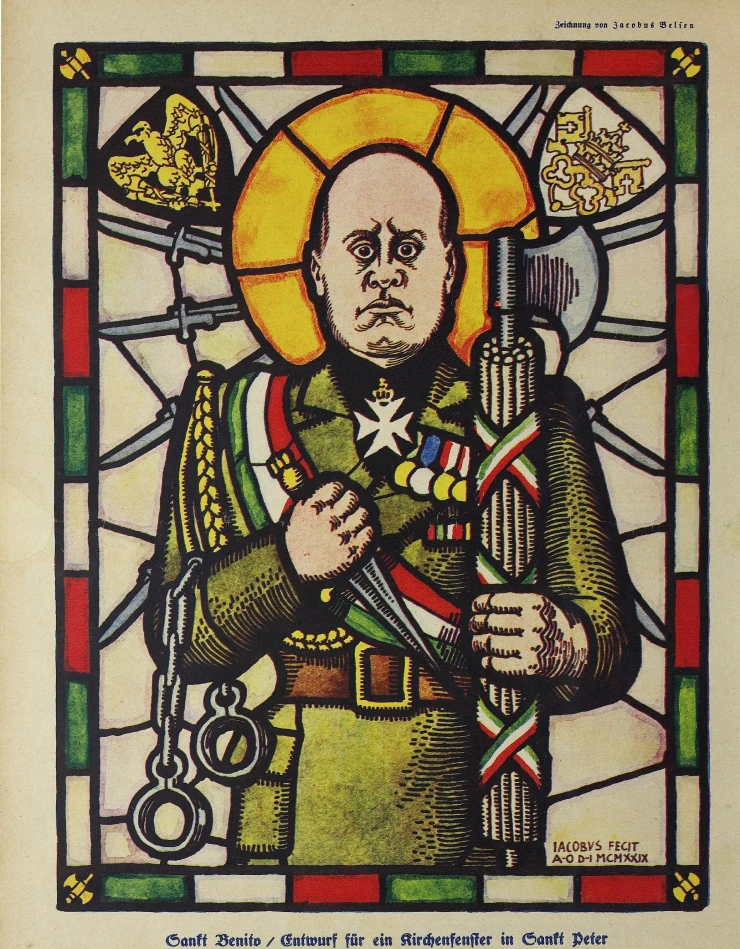

Let’s find that out today by looking at Benito Mussolini attempt at writing a romantic novel. Yes, you read that correctly. In 1910, many years before he would transform into Il Duce, Mussolini wrote an romance. Of course I couldn’t help myself: I had to read it. So today we will discuss this book and answer the question: Is this lustful literature proof of his great penmanship, or should it be discarded, never to be read by anyone ever again?

Mussolini’s literary background

To preface my review, I think it’s important to create a bit of context. Who was Mussolini before he became Italy’s fascist Il Duce?

Humble origins

Well, Benito Mussolini was born in 1883 in a small village at equidistant from Bologna, Florence, and San Marino. His dad was a socialist blacksmith and his mum a Catholic schoolteacher. Little Benito was educated by monks and nuns at various religious schools. He did well and received high grades, although it seems as if his violent tendencies gave him a bit of a bad rep. In these times he was completely captivated by the works of Victor Hugo, most notably Les Miserables. Which he would read in the dark hours of the night in the village barn.

Studying, reading, and writing

At the age of 19, he fled Italy to avoid the mandatory conscription into the military services (oh the great patriot!). He found refuge in Switzerland, where he worked various odd jobs to make ends meet. During this time he read voraciously and attended (without ever being administered) many lectures at famous Swiss universities.

He joined the Italian socialist movement and started writing for the newspaper L’Avvenire del Lavoratore (Future of the employee). From this moment onward he started writing many essays and articles. Virtually all of these essays were of a political or philosophical nature (very surprising, indeed). It is said that his (unpublished) magnus opus would have been a colossal History of Philosophy, were it not that an angry ex-mistress intervened and burned the entire manuscript to ashes.

Apart from all of his non-fictional writings, he only ever published two fictional works. The first one being ‘Null’ e vero, tutto e permesso‘ and the second one being ‘The Cardinal’s Mistress‘. This last story is the one we’ll be discussing today. It was published as a feuilleton in the newspaper L’Avvenire del Lavoratore in 1909, when Mussolini was 26 years old.

So what can we make of this story? Is it the feeble attempt at art that we expect from famous fascist leaders? Or is a hidden masterpiece that predicts a great career in oration and politics? Lets find out.

Review of The Cardinal’s Mistress

Let me start by managing your expectations. The Cardinal’s Mistress is NOT a sexy, hot & steamy, erotic romance. It is much more a political infused romance. Disappointing, I know. I was absolutely hoping to read some raunchy, R-rated stuff, but the best I got was this semi-sensual description of Claudia (the mistress).

Claudia was leaning slightly over one side of the bark and had immersed her hand in the water to enjoy its freshness. Beneath her silken robe was visible the provocative outline of her body, and her white face gleamed beneath her black tresses. Her half-closed eyes understood the sorcery of poisonous passions.

To give you a bit more context to that specific description, let us set the scene.

Setting the scene

The story takes place in 17th century Trento. The protagonists are Emanuel Madruzzo & Claudia Particella. Emanuel Madruzzo is the Cardinal and Archbishop of Trento. Next to that he is also the secular prince of the Trentino. This combination of jobs makes him an extremely powerful man.

As Cardinal of the catholic church, it’s of course very important that you live a celibate life. But what if, next to being a Cardinal, you are also the last remaining heir of a powerful family? Would it then be okay to cancel your celibacy? In order to safeguard your family’s legacy?

The answer is, and I’m paraphrasing the official Papal verdict here: no.

But Cardinal Emanuel Madruzzo disagrees with this verdict, resulting in a 20 year long affair with his mistress: Claudia Particella. Claudia is the daughter of his closest advisor, Ludovico Particella. The Particella family is another powerful aristocratic family in Trento, and together they rule the area successfully.

But when the tide is turning and misfortune befalls the city, the eyes of the plebs fall upon the blasphemous relationship between the Cardinal and the mistress. Do they get angry with the Cardinal for maintaining this indecent relationship? Of course not! This is the 17th century, we’re talking peak-patriarchy! Everyone thinks that Claudia is an evil witch that has cursed and doomed the city.

And thus, what follows is a dramatic story that involves conspiracies, poison, stabbings, murder-plots, and a revolt or two.

Opinion & analysis

The 17th century setting, combined with the flowery prose, makes this story reminiscent of certain classical knight-stories. It feels pretty old-school. But the story is gripping. The lengthy phrases don’t diminish the fact that the tempo of the story is high. A lot happens and you’re never really sure what the conclusion to the story will be.

So yeah, I enjoyed the story. But I also have to be honest: sometimes the prose comes off as overly dramatic. I recall rolling my eyes when I read this following description:

Meanwhile there remained in the banquet hall only the Cardinal and Claudia. The flowers drooped on the table. The plants in the corners of the room had folded their leaves against the close odors of many foods. The abandoned lute augmented the melancholy of the time and place.

Holy crap. That’s the least subtle description of impending doom I have ever read. I mean: it does suit the type of story, but it also makes me cringe a little bit on the inside.

Furthermore, the political presence of the author is hard to miss. He loves to shit on the catholic church. There are lengthy paragraphs where he non-stop lists all his issues with the church. Read for example the following accusations:

“The Church of Rome had indeed set a bad example. The successors to the Chair of Peter were sullied with the most heinous crimes. The Popes synthesized the universal turpitude. Alexander VI of the Borgia family, sinisterly celebrated as a skilled poisoner, was guilty of incest and nepotism. Leo X fixed a tariff for the absolution of sins, and Clement VII maintained a troupe of lascivious women, among them a celebrated African, to solace him in the Vatican. Paul III poisoned his mother. Julius III practiced Greek love. Pius V coined a medal to celebrate St. Bartholomew’s Eve, when the Catholics spilled the blood of some tens of thousands of Huguenots in Paris.”

And this paragraph puts the nail in the coffin:

“If the first rulers of the Church, chosen to promote the spiritual salvation of the people, offered such scandalous examples, how could it be expected that the lesser shepherds should rigidly conform to the evangelical morality of resignation, renunciation and penitence? The entire Catholic hierarchy was infected by the Pontiff down to the last cleric in an Alpine village.”

He continues to sprinkle in little references to his political preferences and his personal background. It’s telling that the elite, the aristocracy and the clergy, are riddled with vices in this story. Even their outward features are rarely favourable. But Mussolini does not spare any positive notes when singing his praise of the peasants. Like when he brings a poor peasant family to the stage for one short scene:

The aged head of the family, with a long white beard, somewhat disordered, and penetrating and vivacious eyes; one of those sons of the soil who possess an iron constitution not to be crushed by long days and years of heavy toil; beside him the eldest son, a square-shouldered masculine type of rustic beauty; his mother, who in spite of her dried up skin and her scanty hair preserved something of the energy of youth.

It is clear that Mussolini is (or wants to present himself as) a man of the people. One can either chose to attribute that to his socialist background, or to his populist and fascist character.

Another nationalist tendency that I picked up on in the book are the many references to classic Italian poets like Dante, Ovid, and Virgil. Even though it’s not necessarily strictly nationalistic to make many references to the classic poets of your mother-tongue, it does feel a bit icky when you know the future occupations of the author.

Finally there is of course the setting of the book. His choice for Trento was not a coincedence. It was the place where he was living when he was writing the book in 1909. But unlike the current situation, where Trento is part of the Italian nation, Trento was in the hands of the Austrian-Hungarian empire in 1909. You can understand Mussolini’s frustration with the fact that this historically Italian city was in the hands of this foreign superpower. This explains the fact that he used Trento as the backdrop of this story. A reference to better times, when Trento was still ruled by Italian princes.

Of course it is easy to put these nationalistic labels on the book in hindsight. It’s impossible to not read the book with the knowledge that Mussolini would later become Italy’s fascist leader. But in all honesty, this book does mostly just feel like a dramatic romance. Not really a political pamphlet. You can read it as a political analogy if you’d like, but why would you ruin a good story like that? I enjoyed reading the book. I don’t think it was bad. It wasn’t extremely great either, but it was an enjoyable story to read. So I can now truly say: I read Mussolini’s romantic novel and it didn’t disappoint.